Git history that helps your team — now and in the future

Background

In the early days of my career, a senior engineer shared Chris Beams' How to Write a Git Commit Message blog post. At the time, we were working in a codebase from the early 2000s, so we often did a lot of code archaeology to understand why things were a certain way. Our team used a typical git workflow where, on merging a pull request, the trunk would retain the original branch's commit history.

Because of this set-up, you could easily see each commit someone had made and, ideally, if they had written good commit messages, you could gain a lot of insight into their thought process. My team at the time made a conscious effort to keep a good git history, so this merge strategy worked very well.

But what happens when you join a team where these habits aren’t the norm?

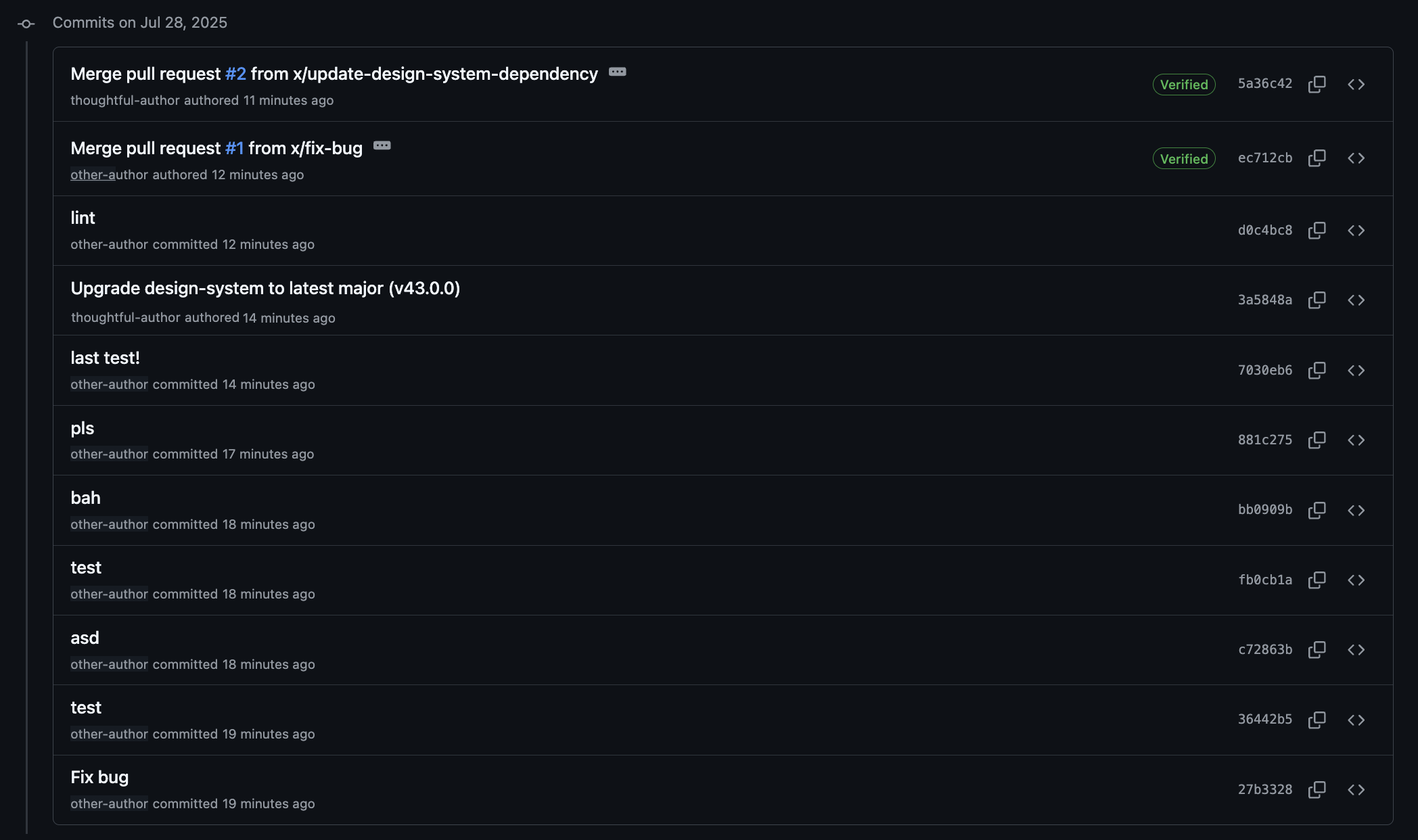

That’s exactly what I discovered in my next role. Suddenly, commit quality was much less consistent across engineers than I had experienced before. Often, I’d find pull requests merged with commit messages like “fix bug”, "test”, "bah", and other unhelpful notes.

Initially, still being a bit green in my career, I tried showing the importance of good commit history and sharing Chris' blog. My new team saw some value in this, but since some hadn't personally experienced the benefits, I could tell that some remained a bit sceptical.

We ended our discussion with everyone saying they'd give it a go, and in the short term, we saw some noticeable improvements. However, some engineers felt that this would add a non-trivial amount of overhead to their workflows, and over time some fell back into old habits (because it's easier, which makes sense).

Why does git history really matter?

I went back to the drawing board and started thinking more about why git history even mattered in my new team. Would improving it help us?

Originally, my views stemmed from working with a really old application where we'd do a lot of deep dives and support work. But in this team, our primary applications were less than five years old, so this wasn't as big of a deal.

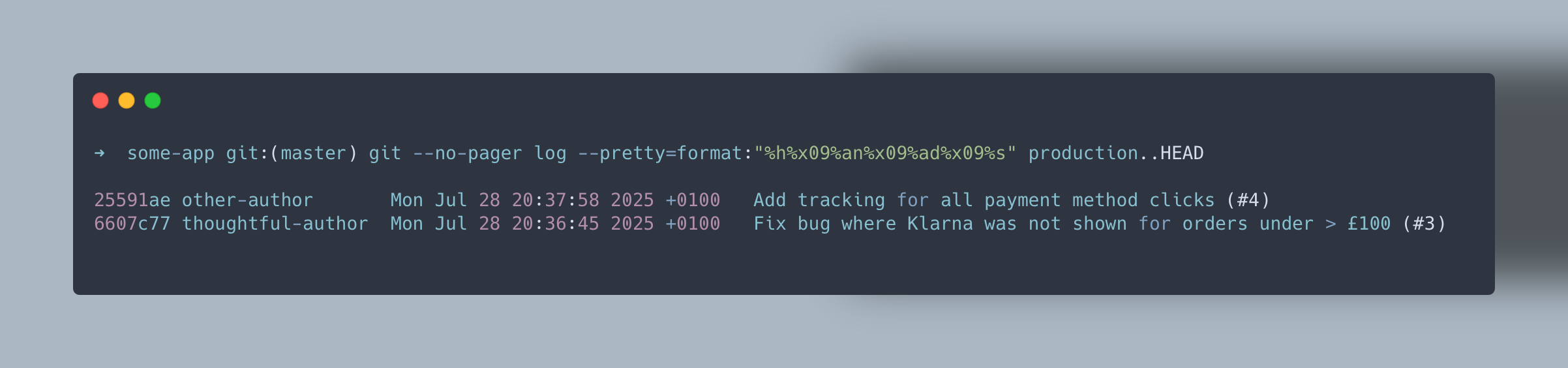

After consciously thinking through where our trunk commit history actually mattered across our processes, the key area was in our release changelogs. As we'd been employing the traditional branch merging strategy, whenever you looked at a changelog, you would see many commit messages even though only one change was going out (sometimes 50+ 🤯).

This was where a change in process could provide true value. The lack of commit quality made our lives harder and also introduced risk of accidental deploys (especially when the change commit log was very long, as shown in the image above). As deploying was something we did every day, improving our trunk commit history here could actually provide noticeable value.

Introducing squash and merge

The first problem to solve was reducing the number of commits on our trunk. I pitched changing our merge method to only allowing squash and merge so that each pull request was 1 to 1 with a commit.

For the unfamiliar: Squash and merge basically combines all commits on a branch into one change when merged, and on GitHub typically retains the pull request title as the merge commit message and a reference to the original PR e.g.

Fix error when server side rendering account page (#123)

This drastically reduced our changelog size and was easy to implement. It was also a low-risk process change, since we could easily revert to our previous merge method if needed.

Switching to this method also meant that rather than our team needing to care about every commit, they simply needed to care about one—the merge commit message (which was typically the pull request title).

This is something we had been doing relatively well anyway, as having good pull request etiquette is an easy way to get your changes reviewed sooner by reducing reviewer effort.

Everyone in our team was much happier with this approach as it allowed engineers to carry out their workflow in the way that works best for them, and we could achieve a clean trunk git history by simply ensuring our merge commit message is high quality.

This also improved our release process and provided a much easier way for us to understand what changes had gone out when. This was also very useful when dealing with incidents or tracking regressions, as I experienced in my original team.

What does a good pull request look like?

These days, I encourage every engineer in my team to ensure that we always have a good pull request title and description for any change. Historically, I've directed engineers to Chris' blog as many concepts still hold up, even if it was written in 2014, but it doesn't always clearly translate to teams using squash and merge. This is the key reason why I've decided to write this blog.

Pitching your change with an effective one line title

When writing a pull request title, the most important aspects to consider are:

Summarise your change in one line. E.g.

Introduce PayPal as a new payment method to checkout. If you find you need to put multiple things into your title, e.g.Upgrade to design-system@60.1.2 and introduce PayPal as a new payment method to checkout, it's a good nudge to consider breaking this into two pull requests. This helps keep pull requests small and changes lower risk (and if you need to revert, you can avoid rolling back both things).Use the imperative mood in the subject line. Imperative mood means "spoken or written as if giving a command or instruction" e.g.

Remove deprecated basket API. This aligns language more closely to how git operates and makes the title read like what will happen when you apply this change. Chris' blog covers this in more detail and I highly recommend giving it a read if you haven't already.Aim to use less than 80 characters. But don't be religious about it—be pragmatic. Your title is meant to be a summary, so if you go longer, it may be a sign that you're getting into too much detail.

Apply appropriate capitalisation, and avoid ending with a period. This is purely to help with readability. Ending with a period is not useful as there are no following sentences.

It’s worth noting that PR titles can be enforced with CI (e.g. with commitlint), but I wouldn’t recommend this outside of shared libraries or open source projects. This allows engineers to make pragmatic decisions when needed.

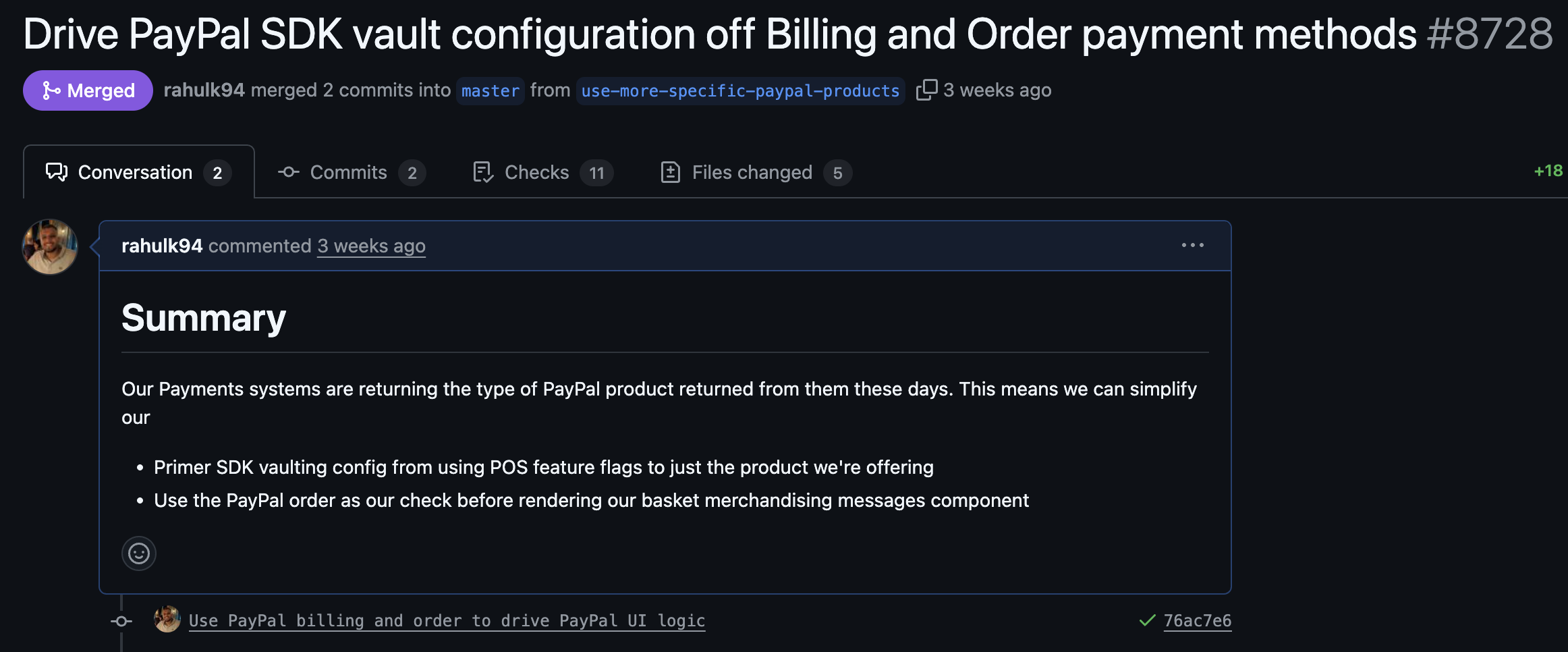

Giving reviewers the context they need with your description

A pull request can be thought of as a snapshot of what is about to change in a system. Reviewers can see what files are changing by looking at the diff, but may not always understand the context behind why we are making these changes, or why they're being done in a particular way.

A good description should, again, succinctly describe what's changing at a high level (think product level, e.g. "Add new payment method to checkout"), and then why we're doing this (e.g. "... as we'd like to experiment with adding PayPal").

Some engineers simply link to a ticket or Jira issue, which is better than nothing, but not always the best way to communicate with your peers. It adds overhead for reviewers, who have to read information in another system, and the link may not always map one-to-one with the pull request. Including relevant information directly in the description makes reviewers’ lives easier and helps your PR get merged faster.

The other gripe I have with not including important context in the description itself and instead linking to your project management system is that those links may break in future. For those who have been with a single company for an extended period of time, it is likely that you have been through a change in project management tooling, e.g. at loveholidays we've moved from Jira -> Notion -> Clickup (over 10 - 15 years). This essentially means after the change in system, those links in old pull requests are now useless. In my view, your version control system is far more likely to remain consistent over time, since it’s used primarily by engineering. Project management tools, on the other hand, often change to meet the needs of other departments.

What about our AI workflows?

You can't write a blog post and not talk about AI in 2025, right? 😂

There have been quite a few new tools in the past couple of years which attempt to streamline the pull request process such as:

- AI generated pull request content

- AI code reviews (e.g. CoPilot, CodeRabbit) – excellent for providing that first feedback cycle sooner for authors

All of these are very interesting and can be useful when used in the right way. However, we need to remember that code reviews are still done predominantly by humans, so all of the above concepts still apply. An AI-generated summary of a pull request is great at describing the what, but is unlikely to be able to give the why of a change. As engineers, it's important to be aware of this and ensure that we're not just giving our reviewers descriptions which don't provide much value versus reading the code yourself.

Commit messages

LLMs are increasingly used in development, including for writing commit messages. This can be a big improvement over previous practices, but as mentioned earlier, if you use squash and merge, the final merge commit message is still the most important.

That’s not to say handing over the commit process to AI is bad. In more advanced workflows with multiple agents, you may need to outsource this to avoid getting bogged down in details.

If you are intending on using AI for committing, consider adding the best

practices described above (or what good looks like to you) to your Claude.md

file (or similar for other tools). While you’re at it, consider adding your

agent as a co-author so it’s clear which commits were AI-assisted.

Benefits of good history with AI

Whilst all the above is useful for ourselves as engineers to be able to better understand and maintain our systems, applying good practices to your git history can also improve LLM understandings. When applying the above best practices, you are much more likely to be able to get good information from an LLM about what's changed in your system over time versus a system where your trunk commit log looks like "Fixing", "Bah", etc.

In summary

Maintaining an easily understandable trunk commit history has many benefits such as simplifying release change logs, aiding in support and incident response work, and when trying to track down when a particular change was introduced.

In the blog, we've covered how you can do this with minimal impact to existing engineer workflows by utilising the squash and merge method and by encouraging pull request best practices.

When writing pull request titles (i.e. your merge commit message):

- Summarise your changes in a one-liner

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line

- Aim to use less than 80 characters

- Apply appropriate capitalisation, and avoid ending with a period

When writing descriptions:

- Focus on the why more than the what

- Be succinct (especially if you're using AI assistance on writing this)

- Don't link to external project management tools if the change can be explained inline instead

- When using AI generated descriptions, ensure it's relevant and not unnecessarily bloated for your reviewers

These best practices should help improve the review process of your team and the quality of your trunk Git history. If this helps your team in any way or you'd like to discuss with me further, catch me on 🦋 rahulkumar.bsky.social.